MOVING MOUNTAINS

I remember, as a young girl, spending my summers with my grandmother in Beijing. She would sing me little ditties in Chinese while brushing my hair with her fingers, my head in her lap. She taught me how to make dumplings from scratch. My dumplings were always too scrawny and so she fixed them into the shapes of sunflowers. Sometimes I would do something I wasn’t supposed to do and my mother, who always took this task solely upon herself, would come after me. To carry out the sentence, solemnly, as if she were a martyr on a journey for my betterment. My grandmother would plant herself firmly between us. I was so shamefully small, crouched under a table or behind a door. My grandmother chastised my mother, “She is only a child, hardly worth all this fuss. You need to learn to control yourself.” And my mother would panic and cry, shoulders shaking, sitting on the edge of the bathtub I would be hiding in. My grandmother always protected me. As I grew older, I realised she did not always do the same for my mother. She chided her for not being a good sister and lectured her on her marriage. My grandmother found fault in almost everything my mother did. After my grandfather died, she lost her will to live. Despite the love of her son, her two daughters, and her five grandchildren - she felt as if she were only a burden. When it came down to it my grandmother was, like her daughter, a martyr. When she left this world, I found myself thinking of how little I really knew of her, her reasons, and her life.

A few years after my grandparents passed, a trunk of their items was shipped to us. In it, a collection of their possessions that are now the only things to piece together their identities and the history of my family. Ironically, the most personal items in the trunk were my grandfather’s hat, an old mahjong set, some old records, a collection of almost 200 Mao pins, a set of government IDs, and my grandmother’s discharge papers from the Red Army. There weren’t any photos.

I try to remember the last honest conversation my parents and I had about our family. We avoid any investigation into our memories. In general, we have always struggled to speak candidly to one another - tiptoeing past cultural need for emotional reticence. Or maybe it was personal restraint since we had always resigned ourselves to the perplexity of immigrant parents and first gen child. So many things unsaid. It seemed like it hardly mattered since we would not have understood one another anyways.

This is where this work begins. Moving Mountains is about reconciliation and recollection. Tracing and reconstructing a family or individual memory that weaves through a collective political and cultural memory. How has an ethos of martyrdom for the people translated into an ethos of self-sacrifice for family? How has scarcity and political distress translated into self-restraint and emotional reticence? How has the trauma, the sacrifice, and the triumphs in the memory of a household influenced its succeeding generations? How do we navigate this memory? Restore it? Reconcile it? Honor it?

This work is comprised of a two channel video installation - my mother making our family dumplings and my grandparents’ belongings here in their new home in America. The video includes short samples from recordings of the first candid conversations my mother and I have ever had of her upbringing through the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). My mother was born in 1963. She and my father left China in the early 80s. The recordings also include tracks from a record that my mother also used to learn English. The record is an English reading of “The Works of Chairman Mao Tsetung.” As a young woman then, she annotated the English booklet that accompanied the record. As a young woman today, I find myself rereading the same passages and thinking about the strict collectivism and the conformity under which my mother was raised. The way she raised me, with filial duty at the forefront. Her constant self-sacrifice in exchange for my freedom and individuality. Character is built through criticism and inevitable suffering.

Also included are still photos of the Mao pins, records, and portraits of my mother; captured in medium format digital and 35mm film. My grandmother spent years on the floor of a factory hand painting thousands of these pins one by one. The Chinese government put hundreds of thousands of Chinese people to work making these pins. Chinese families, who feared punishment, saved them as they would not be caught desecrating an image of Mao. And today, they are passed down to me, a prized “family heirloom.”

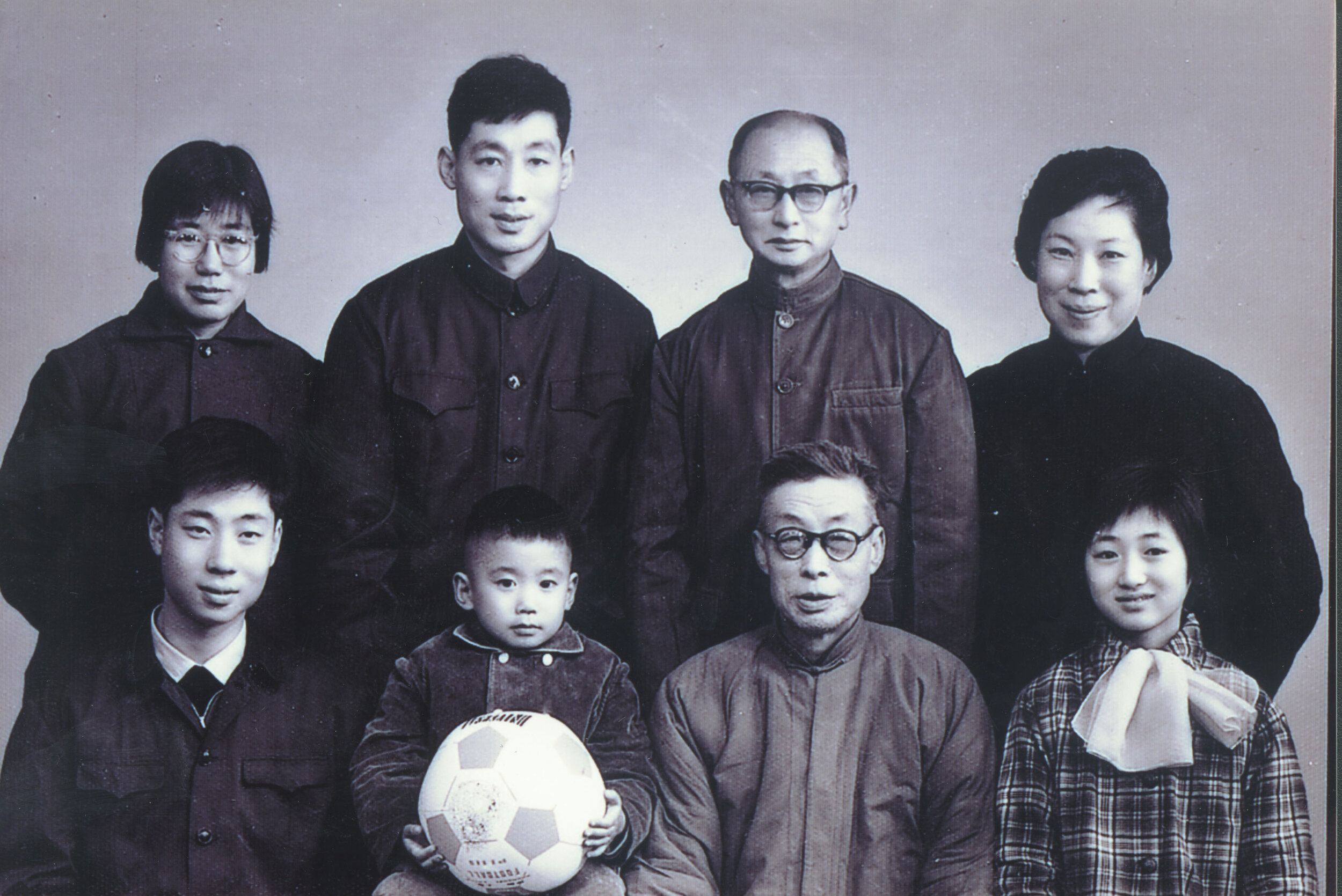

Lastly, a small archive of family photos resides in this work. Some are of older generations, hidden away prior to the revolution out of fear of discovery by the Red Guard. A potential accusation of a bourgeoisie past. This panic forced many Chinese families to burn or dispose of their family photos, and as a result, their visual history.

Grandfather as a child. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Grandmother and her family. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Great-uncle and grandfather. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Great-uncle. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Great-uncle and grandfather. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Great grandmother. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Grandfather's family. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Grandfather, his siblings, and great grandparents. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Grandfather, his siblings, and great grandmother. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Grandfather, his siblings, and great grandmother. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Great-uncle and grandfather. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Great-aunt. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Great-grandmother. Pre-Cultural Revolution.

Aunt and grandparents. During the Cultural Revolution.

Mother and aunt during the Cultural Revolution.

Grandfather and family during the Cultural Revolution. Mother is center.

Grandfather and family. During the Cultural Revolution.

Mother and family. Post Cultural Revolution.

Mother and uncle during the Cultural Revolution.

Mother and family during the Cultural Revolution. Wearing their pins.

Grandparents. Post Cultural Revolution.